The unromantic life of Dumitru Vonica, painter, intellectual, unorthodox self-proclaimed genius, citizen of the world, and archetypal outsider

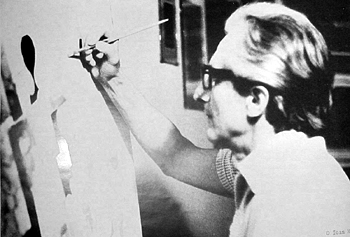

Tica Vonica in his workshop in the 70s.

“I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space” (Hamlet, Shakespeare)

Outline

Dumitru (Tica) Vonica was the fourth child of a wealthy Romania merchant in pre-WWII Cluj, the largest city in Transylvania, Romania. After an almost uneventful childhood, he was exiled with the family during the war years, which did not just bring upheaval, but also freedom to explore on society on the edge. His talent for plastic arts is noticed for the first time. Barely admitted to Medical School, he discovered a passion for medicine. Assigned by the government to a mining town, marrying, returning to Cluj, he invested all his efforts in the next 10 years in an attempt to obtain a medical academic positon. While gifted and committed as professional, he totally lacked social skills and failed, remaining a family physician to the end. At the ripe age of 38, Tica gave up his medical ambitions, and decided to transform his painting hobby into an all-absorbing passion and reason to be. He benefited from the late 50s into the 60s from the cultural thaw between East and West, avidly consuming every artistic news. He became familiar with modern and contemporary French and American plastic arts, as his work in those years bears witness. Never happy as a follower, Tica constantly explored possibilities, changing styles, testing media, interacting with the amateur and professional artists who flourished in those years of hope. When smiles were replaced by tears starting with the 70s, as Romania returned to a now East Asian-inspired proletarian art, Tica was strong enough to follow his path independently and in spite of open official disdain for abstract art, using his medical profession to feed himself and his family. Cloistered in his workshop, he would enjoy vinyl LPs with classic music, and listen every evening to US Congress-sponsored Radio Free Europe, using an American-made transistor radio and a German turntable, both gifts from a French academic and admirer. He avidly read esthetics, looking for a conceptual basis for his own isolation and lack of recognition, and a distraction for the restless, analytical mind easily discernible in the elaborate abstract constructions of his mature years. A map of the Paris Subway adorning an old wardrobe was his trampoline into a boundless universe, where the cold, hungry, grim reality of dying Communism could not reach him. What did bring him down was his own mind: depressions came one after the other beginning with the 80s, sometime interrupted by bouts of mania. Both were major hindrances for his art. In depression episodes he would obsessively read Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, as if Edmond Dantes’s redemption could show a path out of his psychotic torment. When the fall of Communism, which in his manic mood he had been openly predicting since Gorbatchev’s ascent to power, finally did come in a bloody and equivocal way to Romania, Tica barely noticed. A lifelong smoker, he died of lung cancer in 2001, aged 75, ignored by all but the family and a handful of friends and admirers, very much like he expected.

Your guide in this trip will be Alin Vonica, Dumitru’s son and only descendant.

To call my father Vonica, when we share the same name, feels an odd thing to do. For the rest of the story, I will therefore call him by his nickname Tica (pronounce “Teeker”, same ending as in “flower”), like everyone who new him closely used to do.

I was fascinated with Shakespeare since my teens. Many of his thoughts and tribulations felt so close to my experience, and the introductory quote really summarizes Tica’s life. He did live in a nutshell, he was the king of a universe he created, and with his scathing sense of humor he would have relished the irony, and the usual Shakespearean innuendoes. It’s not only about self-delusion, but also about the power of the mind to transcend the mud of everyday life.

And speaking about sense of humor, Tica was famous for his irreverent and biting one, which didn’t spare either himself or his own family, with the notable exception of his mother. Some people who know me, and the family, might take umbrage at the tone of the following account, but none of Tica’s close blood relatives survives, and I would not do justice to his spirit to present things in any other way.

Childhood

Dumitru (Tica) Vonica – even as a child I called him Tica, not “dad” – was the fourth and second to last child from the second marriage of Dumitru Vonica, Romanian merchant of Christian Orthodox confession in Cluj (Klausenburg, Kolosvar, now Cluj-Napoca), Transylvania (Ardeal, Erdely, Siebenburgen), himself the son of a shepherd. Both wives of the elder Dumitru were also born Vonica, but belonged to different strains of the same clan, originating in Poiana Sibiului, a wealthy sheep raising community close to

Ana Vonica, born Vonica, Tica’s mother, in the early 30s.

the historical capital of the German settlers in the province, Hermannstadt (Sibiu in Romanian), and to the Transylvanian Alps (Meridional Carpathians in Romanian). Dumitru senior bought a shop around 1890, and was one of only two Romanians to do so in pre-World War I Cluj. Tica’s mother, Ana, was 18 when she married the 30 years older, fat, but prosperous suitor. Over more than 20 years of marriage, they called each other “sir” and “lady” (“domnule” and “doamna”), an annoying detail that might have had something to do with contrarian Tica’s desire to dispense with formalities.

Tica was born on the second floor of the house with the family shop, on an imprecise date: the birth certificate disagreed with the mother – at the time, official registration occurred when mothers felt like doing it, and births happened at home -, and his Communist identity papers later gave a third date, probably because the Communists did not trust merchants. Tica did not remember, and even before becoming a genius, did not really care, but the date he gave in a handwritten CV was July 17th, the year of our Lord 1924. At that time, the pre-war merchant Vonica Demeter, with a Hungarian only shop sign (the laws of the time “encouraged” non-Hungarians living in the Budapest-governed part of Austria-Hungary to assimilate), had become the merchant Dumitru Vonica, with a bilingual sign, living, with some discomfort, in the newly enlarged post-Great War Romania governed from Bucharest, the “little Paris” beyond the mountains, then as now a cradle of culture, and hotbed of corruption.

Shortly afterward the family moved to a more comfortable villa, on a distinguished street (Erzsebet Uta, Strada Elisabeta, after WWII Strada Racovita, Nr. 45). The living space was organized in a way typical for the Vonica concept of education and intergenerational communication: the first level was rented, the father, mother (in separate rooms), the only daughter (with the mother), and the housemaid (location unknown) lived on the second and most comfortable floor of the house, while the four boys inhabited the separate servants’ house, with one large room, split in two by a curtain. Apparently, the boys were noisy and the patriarch wanted quiet. In summer, the boys moved up the slope of the large, beautiful backyard, to a wooden shed, sleeping among the fruit bearing trees, enjoying petrol lamps and an outhouse, while the main house had electricity, running water, a bathroom and two modern toilets. Tica had the privilege of wearing the clothes his two elder brothers had used before him. They were such rags after him that his younger brother had to get new ones. That sartorial experience had lasting effects, as Tica remained indifferent to his appearance for the rest of his life, only rarely and reluctantly giving in to his elegant wife’s efforts to buy new clothes. He also had to make his own toys of pieces of wood, thread, wires, and rubber, a perfect training for his excellent manual skills, and for his self-deprecating sense of humor: he quickly noticed that kids from families who did not own a shop, a warehouse, six houses rented out, and some agricultural land for good measure (the old Vonica was a believer in real estate), had better clothes, got toys for presents, and probably ate meat more than twice a week.

Tica, a sickly, agitated, smallish boy, grew under the wary and stern eye of his mother, who, unlike the father with four grades, had a high school degree. Both parents, while making money from business, abode by the Transylvanian Romanian obsession with higher education and the respect that was supposed to come with it, a legacy of centuries of formal and informal humiliations for the “tolerated” and “schismatic” budos olah (Hungarian for “stinking Romanian”), and spared no financial effort to get all the boys through college (the daughter stopped after high school, destined to be a housewife), yielding an engineer, an economist, and two physicians. But we are not there yet, the making

Tica, the boy with an exagerrated head, first from left, about first grade, in front of the family villa, on Elisabeta (now Racovita) St., Nr. 45, in Cluj. The villa was never returned to the family, even after the fall of Communism. Next to Tica is Vasile (Lica), his elder brother, then sister Marioara, and in front, sitting, Cornel, the future political detainee.

of “The Tica” (Ticurul – ironic!) had more in store for him.

My father told me a funny story, in as much as deadly peril can be funny, but then all things human were amusing coming from him. When Tica was about 9 years old, he saw a movie after a Jules Verne novel about the conquest of Siberia. The Cossack hero fights with a bear, at one point lifting it up in his arms. Tica went back home, grabbed his four year older bear of a sister, lifted her up, but fell on his back, all her weight on his right thigh, which broke, the bone protruding through the skin in an open fracture. A chronic infection, osteomyelitis, ensued, with pus continuously flowing out. The old Vonica was serious about health (himself a diabetic, he would only shake hands with a glove, to avoid catching infections), and paid for repeated surgical interventions, the way chronic infections were treated before antibiotics. It didn’t help, and, to avoid inevitable sepsis and death, the surgeon proposed removing the leg. At this distressing time, a visiting relative from the countryside recommended filling the abscess with a mix of earth, frog skin, spider web, hair, plants, and other disgusting, more or less organic, materials. Amazingly enough, this inflammatory treatment cured Tica, to his (and mine?) good fortune. The only trace was a deep, large scar on his thigh.

In school, Tica was an earnest, ambitious student, though as long as he stayed in the more elevated environment of the unofficial capital of Transylvania, he was never the best in the boys only class. Some baneful features of his character, namely honesty to the point of naivety, also become apparent at this stage. He once saw in a bookshop a history of the French literature (at that time and in Romania, French was a cultural Adam’s rib that made both intellectuals and socialites, to the annoyance of Tony Judt, author of Postwar: A history of Europe since 1945, which I warmly recommend). Tica boldly asked his rotund dad for the respectable sum to acquire it. “Do you need it in school?” asked the canny elder gentleman. “No!” retorted the clueless son, who obviously did not get his wish. The father only sponsored officially sanctioned spiritual pursuits, not cultural free-lancing.

This little event, which most amused Tica, whose views of his father and his hierarchy of values were less than reverent, was also an early sign of another major, deadly flaw: he was socially inept, to almost autistic levels, incapable of understanding and accepting motives for others’ actions and attitudes different from his own . Throughout his life, he blamed the aberrant environment of Communism, and not human nature, for his social failure, made evident by the lack of promotion and recognition of (as he thought) obvious and praiseworthy qualities and achievements. In his mind, a free society would have inevitably acknowledged his merits, medical and artistic, while Communism forced people to misbehave and ignore him. Alas, the free world has the same assortment of what the French (and some English) call canailles, who would have eaten him alive anywhere, with or without red seasoning. Competition, when it works, laws, when applied, and free speech, when not muzzled by fear of retribution, only limit to some extent the effects of selfishness, ambition, greed, of conceited and desperate mediocrity. In many instances, street smarts beat competence and talent anywhere in the world. In Tica’s views, and in those of much of the Romanian intelligentsia in his time, seeking social interactions for a material, promotional purpose (networking!) was not just unnecessary, but a despicable, damnable way to bypass merit. To my misfortune, I cannot help but feel the same.

Somehow, Tica lucked out by finally choosing art. While temporary fame can be achieved in the art world through a combination of luck and networking, in the absence of real value that fame inevitably fades. Tica’s art belongs to a timeless world of the human spirit and will outlive him, while his social failure will be no more than a biographical detail. Real talent, however, is not exempt from the need of social outreach, since every art needs a public. Tica believed fervently that it was society’s duty to discover him, not his to show off. If this were true, you would have heard his name in high school.

Youth

I know little of his teen years before 1940. At some point he was in love, unhappily, and later praised the virtues of hopeless sentimental pain as a necessary experience for a growing spirit. Raised an Orthodox Christian, with all the ritual implied, he went through a religious crisis, and at some point in the late teens became a freethinker, yet, as he liked to emphasize, indifferent, rather than atheistic.

He was a bemused spectator to Europe’s drift toward catastrophe, and having listened to a Hitler speech on the radio, found it outright ridiculous. Like many Francophile intellectuals, he loathed authoritarian and racist Germany, and all his life yearned for the liberal atmosphere of the 30s, associated with a pro-Western Romania. Others in the country, though, felt differently.

The late 30s saw a resurgence of Romanian nationalism, not only from thugs in the street, but also from right wing governments, including the Royal Dictatorship of Carol II. Old Dumitru’s bilingual firm was replaced, by law, with a Romanian only one, and the policy of “Romanization” of the economy led to the fire sale of mostly Jewish businesses and properties to “pure” Romanians. Dumitru Sr., naturally honest and law-abiding, was outraged by what he considered outright theft, refused to participate, and became increasingly isolated and depressed.

The Vonicas around 1940. From left to right, rear: little brother Cornel, Tica, mother Ana, elder brother Vasile; front row: sister Marioara, father Dumitru, eldest brother Ionel. All have passed away with no other descendants than the storyteller.

In 1940, the Vienna arbitrage conceded Northern Transylvania, Cluj included, back to a resurgent Hungary.

“The Hungarians immediately began a policy of ‘ethnic cleansing’ to diminish the clout of the Romanians in Northern Transylvania. Particular emphasis was given to expelling academics, professionals, and heads of household likely to give coherence to any resistance.” (in Third Axis, Fourth Ally, by Max Axworthy, Arms and Armour Press, 1995)

Although the older Dumitru had been a Hungarian subject before World War I, and saw no reason not to go back to old habits, the family received an eviction order, to be executed in 24 hours (as Tica told the story, the honved – Hungarian policeman – was very polite). It is possible that the family was targeted because of its prominence in the Romanian community, and the parents’ proficiency in Hungarian, to deny potential leaders to the now minority Romanians. The old Vonica, who in the late 30s wrote almost every year a Farewell letter to his children – he had practically retired from business, fell prey to a mild, but persistent, depression, always expecting to die shortly – and never served in any public position, was as wrong a target as he could be. Nevertheless, the next day the family boarded a cattle train, carrying whatever they could, but not the mother. Ana Vonica, using myriad short-term excuses, and her considerable charm and Hungarian language fluency, managed to stay home for the duration of the war, supporting all along the exiled family with money from rents (remarkably, Hungarian authorities, unlike Romanian Communists later, did not confiscate the family properties). The train with the stunned Vonicas could have crossed the border, within sight of the city center, in 10 minutes, but with a calculated twist, the exiles, locked up in their cars, were sent north, then west, then south in a roundabout way through Hungary, to Arad back in Romania, over three days. When the door finally opened, Tica jumped and kissed the earth, his first and last overt patriotic gesture. He would never manifest nationalism, or express any enmity towards Hungarians – whose more civilized and polite individual behavior he respected -, or any other ethnic group. Tribalism meant nothing to Tica, whose heart and mind went far beyond narrow-minded wholesale classifications of human beings.

It would be reasonable to imagine that the years of exile were terrible for the young Tica. But then, he was an oddball, and actually thoroughly enjoyed the lack of supervision, and the opportunity to explore new people and ideas. He also learned about the futility of material possessions, which the later shock of Communist take-over only strengthened. Refuge could very well have been the crucial event that unleashed his mind.

The family split to survive. Using a large network of relatives, each member stayed in a different location, both in Transylvania and in the ‘Old Kingdom’, pre-Great War Romania, to the south (Wallachia/Tara Romaneasca). Tica went first to Tirgu Jiu, a town associated with Constantin Brancusi, whose Ensemble there – “Table of Silence”, “The Gate of the Kiss”, and “The Endless Column” – he visited, and thought nothing of it. The late 19th century neoclassical equestrian statue of Hungarian king Mathias Corvin in downtown Cluj was far more impressive to his immature eye (as he typically noticed, “the horse was the best, it even had everything between the legs”). Tirgu Jiu saw the first official acknowledgement of his artistic talent: his drawing of Myron’s Discobolus received a prize and was exhibited in his high school.

Tirgu Jiu was also the place where Tica had his first unpleasant encounter with political realities. 1940 was the peak year for the Romanian extreme right party, the Legionnaires. In high school, the only empty seat in the assigned classroom for the newly arrived refugee was at a rickety desk in the back, next to another student. The youngster presented himself (his family name might have been Novac), and mentioned that he was sitting there because he was Jewish. Tica replied he had been exiled because he was Romanian, had no problems sitting next to a Jew, and they became friends. Sometime later, a group of elder kids, the Legionnaire cell in the school, approached the diminutive Tica, telling him to move away from the Jew, or else. He refused, and escaped retribution only because of his refugee status.

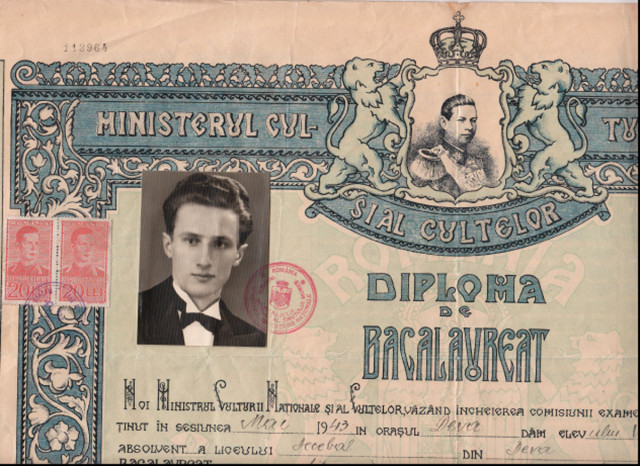

Tica at 19, High School Degree Diploma, 1943, Deva. His best picture ever.

For 12th grade, in 1942, Tica moved to Deva, back in Transylvania. He became, through his academic prowess, a local celebrity, and his graduation – the end of high school exam, the baccalaureate, was open to the public – was a social event that a few Deva natives recollected many years later for my benefit. His Diploma listed the grades for all study subjects during the high school years, and at a time when grade inflation did not exist, his only Exceptional was in the Arts.

’43 was a war year, Romania was a German ally, and 19 year olds were to be drafted, unless admitted to college. While Tica was brilliant in Deva, he was much less so in the country as a whole, and, lacking both focus and drive, he barely managed to get accepted by the Sibiu Medical School, which was actually the Cluj Romanian Medical School in exile. The lack of interest did not end there, and he failed a number of early exams, which, lucky him, he was able to pass before the end of his studies (Romanian Medical School then, as now, was a college accessed directly form high school, but required 6 years to complete). Tica told me the story of his Anatomy exam, passed in his 6th year (Anatomy was taught in the first two years). A famous professor, Papilian, gathered a detachment of failed students who desperately needed to try one last time, had them come every day over the 1 month long summer exam session, to just hang out dry while he was examining the younger students. Only when he was done with the regular examinations, did he deign turn to the slackers. Tica passed, barely, and got his medical degree in 1949.

What changed his life were the clinical years. By 1945, in now Russian occupied and Allied Romania, the Medical School, and the Vonica family, returned to Cluj. The father had died in 1944, in his ancestral village, a broken man and a victim of the lack of insulin during the war. Tica, though, now an intern, was flourishing, thrilled to work with patients and solve the riddles of diagnosis, guided by two professors of national fame, Iuliu Hatieganu and Ioan Goia. Those happy, intense years took a break during the Students’ Strike of 1947(?), a move in support of King Mihai (Michael) the First, who was trying to thwart the slide of Romania toward Russian-imposed Stalinist Communism. Tica, like many other students in Cluj, would gather every day in the city center and chant “The King”, until they were hoarse. The strike failed, the students were beaten up by workers with sticks – ironically saved by Russian troops, whose commander placed his desire for order above class fight – and Tica lost his internship. He was, nevertheless, able to enter through the window when the door was shut, and surreptitiously resumed his clinical work.

The end of medical school came as Communist rule started in earnest, the most clear sign being that students every now and then were disappearing, nobody knew where, but most likely in the bowels of the burgeoning universe of political jails and camps. The point was less to punish individual misbehavior than to instill an all pervading fear, and it worked. In the late 40s – early 50s, if you were arrested by mistake you got 3 years.

Medicine, the first passion

I am not sure how Tica ended up in Baia de Aries in 1950, a mining town in the heart of the Western Carpathians, West of Cluj, so I cannot say if he was sent there because of his “unhealthy social origin”, meaning, in Communist slang, because his dad had been rich and his blood had to be bad. By now, all properties had been nationalized, but if you ever had had an employee, you were an “exploiter” for ever, and while Stalin sent people to the Gulag for believing in genetics as basis of heredity, as an old Orthodox seminarian he did believe there was such a thing as an indelible Birth Sin.

The problem was the absence of any official, open way to come back from there. But why would Baia de Aries be bad for Tica? Well, the devil is in the somewhat troubling little details of a poor, backward country like Romania. There were only dirt roads in the area, and the best way in was a narrow gauge steam train (the mocanita) that took forever to get there. The only building with electricity was the doctor’s office, water was from wells and the toilet was an outhouse. Most disturbing for the mentally hectic and highly interactive Tica, there was not much of an intellectual company there – many locals were actually illiterate -, and no radio either (TV did not exist), only the Communist press blasting the capitalist American warmongers, whose ultimate, crushing defeat was, like the End of Days for some American Christians, always just around the corner. The solution was a willing victim, a forestry engineer and a good friend for the rest of their lives, whom Tica would place on a chair, his back to the wall (no hope of escape), and would deliver long speeches to, on whatever subject troubled him. This was possible due to the endless forbearance of Titi Dominic, the friend, who stoically, or naturally (spare talk is a Transylvanian virtue/flaw, depending on your point of view, which obviously eluded garrulous Tica), said nothing for hours.

Two other amusements were available there. One was drawing, which Tica embraced as a hobby, and the other was ladies, which he embraced differently, another life long interest that fit with the end-of-the-world atmosphere of postwar Romania, where males in his generation had been decimated by the war, and the constant threat of arrest for real, or far more often imaginary political offenses, loosened

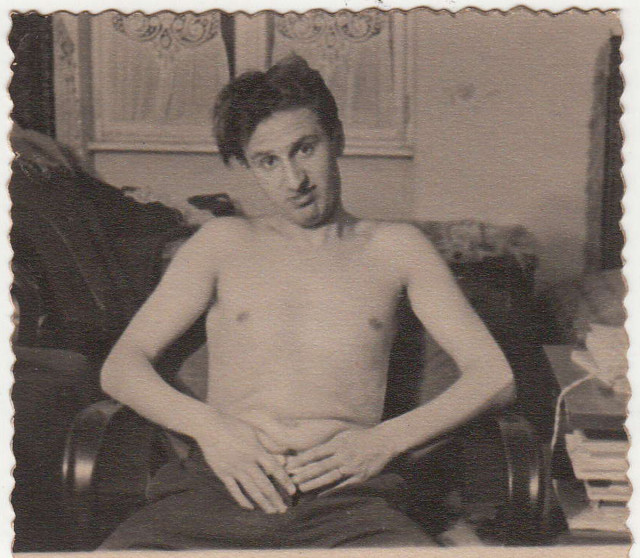

Funny Tica, undated, in the family home, maybe around 30 years old

previously uptight mores. That latter occupation had a family tradition (I know actually more about what the old Vonica did), but it might have been connected to Tica’s hypomanic temper, and therefore shared the same source of irrepressible energy with his passion for medicine, and later for painting.

Tica stayed three years in Baia de Aries, and in the last one he married.

The first time he saw Zoe (Zizi) Diaconeasa, the future wife, was momentous. They were biking toward each other when, bewildered by her looks, he lost control and fell, while she continued her ride, laughing. She was intelligent, cultured, well mannered and good looking, while he was a bit of an exotic country bumpkin, but compensated by enormous determination. Tica practically besieged Zizi with attentions and very soon his boldness and insistence to marry him paid off: she was completely unsettled in a strange environment, he was educated and looked so self-assured, that she said yes, to deep, but belated, regret.

Zizi was the youngest daughter of the poor niece of a Greek merchant from an established, but staid family, and of the richest man in Pitesti, her birth place and main town of Arges county, no far from Bucharest, in Tara Romaneasca. Her father was an American-style self-made man, with great energy, irresistible charm, daring (in the 30s, to his wife’s despair, he repeatedly mortgaged the family house to secure loans when he saw business opportunities), ruthlessness, and uncanny business instinct, which propelled him from store clerk to millionaire. Like Tica’s dad, he also sent his three kids to college, but Zizi, the youngest, was of college age at the worst moment: while she was passing her high school graduation, her father had been arrested on suspicion of hiding riches and beaten up in the basement of his own house, which had become headquarters for the local Communist Security Service. He ran away from Pitesti to the capital Bucharest, where, after a stint at wood box making, he managed, God knows how, to acquire a weekend cottage in the suburb of Baneasa. When Zizi applied for admission to the Medical School, her dad had therefore become a farmer. That was not enough to escape the recently passed law that forbade the children of people of unhealthy social origin (apart from business people, many white collar workers, from physicians to engineers and university professors, were also included, but the largest contingent were farmers who owned more than the minimal surface of workable land – the “chiaburi”) from attending college. Zizi’s admission test was rejected unopened – she had been the valedictorian of her high school class – on ground of her ‘bad file’, where all subversive inheritance and careless statements less than positive about the government were carefully recorded for official use.

Scared to death that without higher education she might end up working in a factory for the rest of her life, she found a college that didn’t care who she was: the just-founded Maxim Gorki Institute for Russian Language and Literature, meant to prepare teachers to spread the “light coming from the East” to the ignorant Romanian masses, in Russian. Remember that Romanians went from hearing everything was terrible about Communism and Russia, which Romanian arms fought until late August 1944, to (enforced) worship and admiration for all things Communist and especially Russian (that was the time when Russian dwarfs were the tallest in the world – those who thought this was funny got 10 years -, and no human inventions from the wheel on originated outside the Russian steppes and the Russian language) four years later. So, Zizi took her hatred of Russian occupation and complete ignorance of Russian (French was her foreign language) to the Russian Language College. For the first exam she managed to learn the alphabet, but not much more, and memorized the textbook by heart without understanding a word. When drawing a question to talk about, she started blurting out from the beginning of the textbook (which probably was the introduction). The professor was so impressed with her effort and memory that he forgave her for not knowing any Russian. After 4 years in college, she was a fluent speaker, and an admirer of 19th century Russian literature. Her file probably had something to do with her government job in Baia de Aries, at a time when teachers of Russian in Bucharest high schools might be barely literate, as long as their social origins were healthy.

Begged by friends in Bucharest to stay put and wait for a better time, she again let fear of retribution take over, and moved to the countryside, where people were not just poor, but spoke an unfamiliar Transylvanian dialect that made adaptation even more painful. Her mother accompanied her, but when she saw the living conditions she sobbed uncontrollably, and was swiftly shipped back home by the differently tempered daughter, who had inherited from her dad, if not the social skills, at least the pride. On this background, Tica, disheveled, agitated, big nosed, but absolutely certain of his goals, actually appeared like a prince charming on a white horse (bike?), ready to rescue the desperate princess from the claws of bad Romanian and dirt roads.

She said yes to marriage, and surprisingly enough, for once, Tica pulled a social stunt. He moved back from Baia to Cluj against all odds.

Every year, there was a Hygiene Inspector, himself an M.D., who would drop by Tica’s office, talk to him pleasantly, tell him how he should be practicing medicine in an academic hospital, always ending with “just drop by my office in Cluj, and I’ll help you”. Tica didn’t take that seriously, until love and despair drove him to an act of bravery: he resigned his office, packed everything up, including the new wife, and luggage in hand he actually showed up at the horrified inspector’s office. He ended up with a hygene inspector position, before becoming “factory physician” for a state owned industrial cooling equipment company (Tehnofrig), a job he kept for more than 20 years.

The couple moved to the Racovita Street villa, where by now the family – Tica’s mother, sister, and younger brother – were living in 2 rooms of the nationalized house, sharing the bathroom with two families placed there by the regime on the same floor. Tica and Zizi got the corner room, which offered some privacy, but had to pass through the other, with its three inhabitants, to get to the hallway and the bathroom. That was the room I called home for my first 9 years.

Stalin’s death in ’53 brought a sort of thaw, and some news from beyond the iron curtain. Tica went back to hospital work with a vengeance, spending 3-4 hours a day as a volunteer physician after his regular 8 hours, in the same academic hospital where he had been an intern. He wanted to be a hematologist, putting together a draft for what was supposed to be the first Romanian Hematological Atlas, for which he drew the pictures directly from the microscope slides. I also found a paper written for a national medical journal, on back pain, a condition that he himself suffered from. The fifties are the first period when his interest in plastic art appeared to have become more systematic, with many watercolors and drawings (portraits and landscapes).

Things changed again, for the worst, after the failed Hungarian Revolution of ’56, which my parents followed on the radio (they begged the world to help them, until Russian troops took the broadcasting station). The wave of destalinization launched by Khrushchev stopped cold, and the same bad old Romanian Communist Chief, promising stability, kept his place and triggered a new, preventive wave of arrests. In January 1959, there was an unauthorized student demonstration, celebrating the union of Wallachia and Moldavia (from 1859!), which formed the basis for the modern Romanian state. While the occasion was innocuous in itself, everything spontaneous had to be subversive, and every participant was arrested and “convinced”, physically (back then, pulling nails was more popular than waterboarding among the reds), to reveal the necessarily larger conspiracy. An arrested literature student knew Tica’s younger brother Cornel, a pediatrician with a passion for writing poetry, and he was soon interrogated by the Securitate. The Vonica’s estates (two rooms) were thoroughly searched. My parents had a prewar map of the Romanian seaside shore, which they used when driving there by motorbike, but this was illegal (all maps were proof of collaboration with American spies who dreamed of Black Sea vacations), so they bounded it with a sowing thread and hung it out the second floor window. While the search was ongoing, the thread snapped and the book fell with an audible thud. The officer did not notice, and no additional arrests were made. Cornel was essentially found innocent, and received 1 1/2 years (they were mellowing, that was instead of the 3 years in the early 50s). He visited some great political jails, met numerous cultural personalities – Communist jails loved intellectuals, which might explain my reaction when I read in a Texas small town sheet about “the liberal intellectual Communists in Washington”, meaning the first Clinton administration – and even the first Danube-Black Sea Canal, which had (re)educational, as opposed to economic, purposes. He discovered he was gay – the Communists, like all reds then as now, hated, outlawed and enthusiastically jailed homosexuals – and how to stop the pangs of dysentery by eating plaster scraped off the walls.