Conversation in front of an abstract painting, between the artist and a bewildered onlooker:

“What does this represent?

– Cows grazing a lawn.

– But where is the lawn?

– There is no lawn left, the cows grazed it.

– But where are the cows?

– What would the cows do there without a lawn?” (French joke)

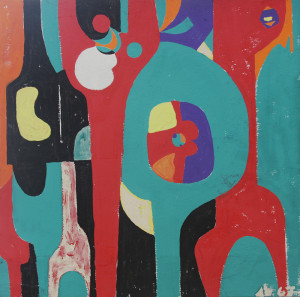

Duco 1967 / 1bis

Vonica always believed the object of the painting is of no consequence. If you want to see a flower or a stool, you can look at it live, or get a photograph. What makes a painting special is “style”, the way an artist combines his peculiar hand trace with chosen shapes and colors. It’s not the flower, or the stool, or the nude, it’s how they are painted. This “how” is what you are looking for, and abstract painting, devoid of the figurative “story” and its rational content, lays it bare, for better or worse.

If you are born with a natural skill for shapes and colors, you don’t need any other help than your enthusiasm for seeking art and discovering it intuitively. Your mind will find on its own ineffable cues, meanings and pleasures in a work of art. A house painter once came to Vonica’s apartment to fix a wall. His work done, he was trying to leave when he lost his way and entered Vonica’s workshop. This man, a country bumpkin without high school, who had never seen anything more than a church icon as painting, was struck in amazement and could hardly move, or utter a word, for a few minutes. “This is so beautiful”. That simple man had a godly gift, and abstract art spoke to his naïve, unprejudiced soul without the need of introduction.

If you, like mine, have a less obvious skill than a house painter, try something like this.

Almost any painting is a game of lights and colors molded by shapes. Let it draw your attention. If you notice a focus, or a direction, of light, follow it, dive in it, look for its details, then look for centripetal clues leading away from it: a second, more discreet focus of light next to it, a shape moving from light to dark, a gradient of color moving away. Go with it to the new destination, and restart the process of looking for details and new directions. As you do this, the painting will no longer be a static canvas, but will come to life, transforming space into motion and time, uncovering itself to your esthetic senses, beyond reason, in pure ecstasy.

Almost any painting is a game of lights and colors molded by shapes. Let it draw your attention. If you notice a focus, or a direction, of light, follow it, dive in it, look for its details, then look for centripetal clues leading away from it: a second, more discreet focus of light next to it, a shape moving from light to dark, a gradient of color moving away. Go with it to the new destination, and restart the process of looking for details and new directions. As you do this, the painting will no longer be a static canvas, but will come to life, transforming space into motion and time, uncovering itself to your esthetic senses, beyond reason, in pure ecstasy.

After exploring the lines of force, the contrasts, and the internal dynamic of the painting, go back to the whole, sweep the painting from different directions, from the sides, or the center, from the foci of light, or darkness. After experiencing the details, the whole will appear radically different, nuanced, and complex. Notice how waves of color confront or blend with each other, how details turn into larger masses, how shapes and colors channel your sight into currents and eddies. As I describe this, I think of the painter who made me discover the internal motion of a canvas, Turner, one of Vonica’s favorites.

Another crucial dimension, very hard to capture in a reproduction, is the depth of the painting. Antique and classic masters used perspective for the impression of space. Another way is through multilayered colors, used extensively by Vonica, which create different effects depending on the surrounding light and the view angle. Move around the painting, if you are in front of the original, see how unexpected depths reveal themselves. Go back to the central position in front of the painting, and look again, with a newly trained eye, noticing shades and details you missed initially. You will notice how the overlapping transparent colors combine with the detailed, overlapping geometric shapes to break the flat surface of the painting in a maze of dizzying chasms.

Another crucial dimension, very hard to capture in a reproduction, is the depth of the painting. Antique and classic masters used perspective for the impression of space. Another way is through multilayered colors, used extensively by Vonica, which create different effects depending on the surrounding light and the view angle. Move around the painting, if you are in front of the original, see how unexpected depths reveal themselves. Go back to the central position in front of the painting, and look again, with a newly trained eye, noticing shades and details you missed initially. You will notice how the overlapping transparent colors combine with the detailed, overlapping geometric shapes to break the flat surface of the painting in a maze of dizzying chasms.

Since this particularly spectacular feature comes out poorly in reproductions, you will have to make an effort of imagination to fully appreciate the intensity of the experience. Vonica was an exquisite art lover, capable of mentally reconstructing a masterpiece from the hints present in at best mediocre reproductions available to him. Most of those reading this have much more experience than he ever had with the great museums of the world (actually, he never saw any, besides a couple of itinerant exhibits, and the less than opulent museums of Romania),and might be able to grasp the subtleties of Vonica’s works..