The technique in the painter’s words

“I paint on filter paper or cardboard-glued paper, in approximately 6 layers of colors, the final two being applied with gaze wetted in diluted color, which allows me to obtain transparencies that a paintbrush cannot produce.” (Letter to Andrei Plesu, 1987).

“Yes, light, color, but also space and time. I achieve them through a richly colored chiaroscuro, with light economically distributed, like a directed explosion. I solve the sensation of space without perspective, through variations of colors and hues, producing depths and bursts toward the surface, on an often neutral background. Time is suggested by geometric forms, with straight lines alternating with curves which multiply, fragment, come out of painting frame, bestowing – I hope – a sensation of boundlessness and flow of time.” (in The Danger of Confession, by N. Steinhardt, 1993)

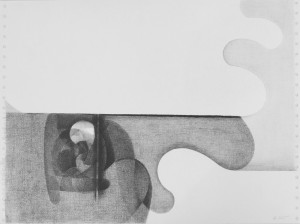

Drawing 1975

Thinking

but the simple fact is that would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified, more supremely noble, than this very poem, this poem per se, this poem which is a poem and nothing more, this poem written solely for the poem’s sake

(E. A. Poe)

Oil 1960s / 7

In his almost 40 years of furious activity, Vonica followed his own lights, a stubborn and convinced follower of art for art’s sake. While the English translation of the original French (l’art pour l’art) introduces a note of sarcasm, the phrase shined like a promise of Heaven in the dark bowels of Communism, where Vonica spent almost all of his creative life. Since he was not dependent on his art for a living, he could afford to reject both the government-imposed “socialist realism”, by which most official artists had to abide, and the constraints of fashion and public taste, which govern commercialized art. Vonica benefited, ironically for the crushing, dull oppressiveness of Soviet-style rule, from total freedom to enact his artistic will, and paid for it with almost complete isolation.

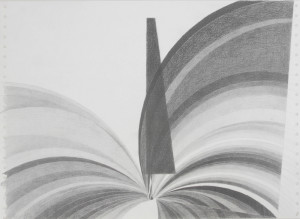

Drawing 70s-90s / 60

We live in a time when “elite” has become a dirty word in America, and ever fewer young minds are exposed to the refinement and complexity of the traditional forms of art. A cultured person no longer enjoys the intellectual cachet of old, passing for a freak outside small like-minded groups of experts. In 2014, the President of France declared Soulages the greatest living painter. A BBC reporter was wondering who in the world knows about Soulages, and his (mostly) black-painted canvases. Vonica did, and he thought Soulages was a giant. An impassionate lover of fugues and chamber music, voracious reader of esthetic literature, who made no secret of his intellectual pursuits, holding by the button any stranger met at parties, to lecture the despairing victim on the changing balance between intuition, affectivity and sensitivity in the various masterpieces, would hardly be the man of the moment. The ridicule of his social attitudes now gone with those who witnessed it, all that is left is the work sampled here. As he liked to say, a finished painting no longer belongs to the artist, it begets its own life. And that, I would add, is the province of the spectators, without whom no art can exist as art. Whether Vonica’s polyphonic, spectacular, yet subtle work will become part of the perennial treasure of humanity, transcending time and geography, is now up to the art lovers, and the Web..